BLUES JUNCTION Productions

7343 El Camino Real

Suite 327

Atascadero, CA 93422-4697

info

- Home

- Letter From the Editor

- Tom Hyslop: A Personal Appreciation

- Top Ten Albums of 2022

- Dave's Top Ten List of Top Ten Lists

- An Appreciation of James Harman

- Album of the Year: The Duke Robillard Band They Called It Rhythm & Blues

- Album Review: Rick Holmstrom Get It!

- Album Review: The Phantom Blues Band - Blues for Breakfast

- Album Review: Bob Stroger & the Headcutters That’s My Name

- Album Review: Hash Brown - Stop! Your Evil Ways

- Archives

- Contact Us

- Links

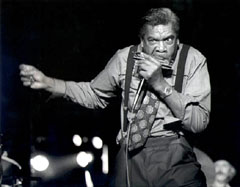

George "Harmonica" Smith

by Dennis Gruenling

One of the first things that come to mind when people think of the blues is wailing, amplified harmonica. There are four pioneering fathers of traditional blues harmonica, the two “Sonny Boys” and the two “Walters”.

John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson was really the first true originator of what’s now known as Chicago style harmonica playing and was a true pioneer with the harmonica He utilized the instrument as a single note and lead instrument in blues like no one before him. Rice Miller aka “Sonny Boy Williamson II”, who recorded for the Trumpet & Chess labels was also a pioneer for his approach to the harmonica, as well as his songwriting skills.

known as Chicago style harmonica playing and was a true pioneer with the harmonica He utilized the instrument as a single note and lead instrument in blues like no one before him. Rice Miller aka “Sonny Boy Williamson II”, who recorded for the Trumpet & Chess labels was also a pioneer for his approach to the harmonica, as well as his songwriting skills.

“Little Walter” Jacobs and “Big Walter” Horton are both widely recognized for their contributions to the blues world and their place in blues harmonica history as well. Little Walter was known as the king of amplified Chicago-style harmonica. His wildly imaginative approach to  improvising and his masterful songwriting skills became the hallmark of his career. Big Walter is renowned for his massive tone, great use of dynamics and rock solid tongue blocking techniques.

improvising and his masterful songwriting skills became the hallmark of his career. Big Walter is renowned for his massive tone, great use of dynamics and rock solid tongue blocking techniques.

The next generation brought the likes of Junior Wells, James Cotton, Carey Bell, Charlie Musselwhite and Paul Butterfield, among many others. However, there is one player not mentioned above, whose name continues to pop up in conversation when present day masters such as Rod Piazza, Kim Wilson, Al Blake, Steve Guyger, and Mark Hummel talk about their influences. This man was also hugely influential to modern day, yet deceased masters such as William Clarke & Paul de Lay. This man is George “Harmonica” Smith.

Allen George Smith was born on April 22, 1924, in West Helena, Arkansas. His family moved to Cairo, Illinois, soon afterward, where he was raised. Under the tutelage of his mother, Smith first put harp to mouth at the tender age of four years old. The youngster started playing professionally at local parties, juke joints, and on the street within a year or two. By his teens, he had moved away from home and travelled throughout the south. He spent most of 1943 singing and traveling with the Jackson Jubilee Singers who were based in Jackson, Mississippi. With this group he incorporated his harp playing occasionally.

In 1949, Smith moved back to Chicago. He soon started working with a young Otis Rush, who was then playing a style of blues similar to that of Muddy Waters. After Henry “Pot” Strong, Muddy Waters’ harp player, was murdered on June 3, 1954, George was asked to replace him in Muddy’s band. The group went on tour throughout the south. Upon returning to Chicago the band worked clubs like the Zanzibar Lounge on a regular basis.

George’s recording debut occurred when he backed up Otis Spann in October of 1954 on his Checker single It Must Have Been the Devil. The real breakthrough, however,  came later that year at his next session in Kansas City. Under the name “Little” George Smith, the songs Blues In the Dark and Telephone Blues were released on the RPM label. Both recordings are masterpieces of blues harmonica. Blues in the Dark with its fat-toned chromatic work and Telephone Blues with George’s trademark tremolo octave introduction seem to set a new standard for phrasing and tone. These songs also are significant examples for his playing in what is known to harmonica players as “third position”. This means the player is playing in a key a whole step up from the key of the harmonica. In fact on almost half of the titles that Smith recorded for RPM, he played in the third position. Tunes such as Blues In The Dark, Oopin’ Doopin’, Doopin’ and Down In New Orleans are examples of Smith’s stellar chromatic harp playing. On the other hand, songs such as Telephone Blues, Blues Stay Away and Rockin’ are all recorded with Smith using the smaller diatonic harp. George had not only mastered third position, but created a whole new approach for this on the harmonica, especially when playing the chromatic.

came later that year at his next session in Kansas City. Under the name “Little” George Smith, the songs Blues In the Dark and Telephone Blues were released on the RPM label. Both recordings are masterpieces of blues harmonica. Blues in the Dark with its fat-toned chromatic work and Telephone Blues with George’s trademark tremolo octave introduction seem to set a new standard for phrasing and tone. These songs also are significant examples for his playing in what is known to harmonica players as “third position”. This means the player is playing in a key a whole step up from the key of the harmonica. In fact on almost half of the titles that Smith recorded for RPM, he played in the third position. Tunes such as Blues In The Dark, Oopin’ Doopin’, Doopin’ and Down In New Orleans are examples of Smith’s stellar chromatic harp playing. On the other hand, songs such as Telephone Blues, Blues Stay Away and Rockin’ are all recorded with Smith using the smaller diatonic harp. George had not only mastered third position, but created a whole new approach for this on the harmonica, especially when playing the chromatic.

Little Walter had used the chromatic harmonica before in a blues context, backing up Muddy Waters on such tunes as I Just Want To Make Love To You, I’m Ready and Smokestack Lightnin’. These selections pre-dated his own recordings Lights Out and Fast Large One from 1953 and Blue Light from 1954 in addition to a few other, then unreleased tunes.

Smith, however, had his own unmistakable sound and voice on the chromatic that were full of fat tones, chords and octaves. Other chromatic gems Smith recorded later on include his backing of Sunnyland Slim on Got To Get To My Baby from Slim’s album Slim’s Got His Thing Goin’ On for World Pacific Records and two other of my personal favorites, Hot Rolls on Lapel Records and Tight Dress on the Sotoplay label.

Smith even learned to play some standards on the chromatic, such as Misty, Summertime and Peg o’My Heart. This erudition in no way took away from mastery of his diatonic second position playing. Fine examples of this playing style can be heard in California Blues on RPM, Blowing The Blues on Carolyn, Loose Skrews on Sotoplay and one of the most over-looked blues harmonica classics, Sharp Harp with Champion Jack Dupree on King.

One of the techniques George used on diatonic, as well as chromatic, that made his style and sound stand out, was his use of octaves. Using the tongue blocking technique, he played two notes an octave apart on either side of his tongue. When this technique is performed correctly, it makes for a BIG sound,  especially when coupled with a throat tremolo, as George sometimes did to great effect. In other instances he would get a beating or vibrating sound by playing an octave, caused by one of the notes being slightly out of tune with the other. He also had a great talent for building up a solo and knew just when to release the tension musically, sometimes with a big, intense, vibrating octave.

especially when coupled with a throat tremolo, as George sometimes did to great effect. In other instances he would get a beating or vibrating sound by playing an octave, caused by one of the notes being slightly out of tune with the other. He also had a great talent for building up a solo and knew just when to release the tension musically, sometimes with a big, intense, vibrating octave.

A terrific example of this is his instrumental Juicy Harmonica from the album Of The Blues. During the first three choruses, he lays down some nice wailing harp. By the fourth chorus, he starts to build up the tension, which peaks in the last four bars when hit repeatedly he hits an octave on the downbeat. The song comes to a climax and releases tension in the fifth chorus. He starts with an even higher octave and gets that awesome, vibrating sound, which really grabs the listener.

Another thing George really had a knack for was building tension by repetition. This should not be confused with repetition for the lack of knowing what else to do. He would play a theme for a while, then play it, come back to it and twist it around until you were on the edge of your seat. As the late Paul de Lay would describe it, “You’ve got to stick with an idea or theme long enough to let your audience enjoy it with you. The all-time champ of that would have to be George “Harmonica” Smith. He could play something simple and keep it coming at you until you didn’t want it to stop. It’s probably the most satisfying and effective playing I’ve ever heard.”

After his initial recordings for RPM, George traveled and performed as part of a Universal Attractions touring revue that also included Margie Evans, Little Willie John, Champion Jack Dupree, and Hal Singer & his orchestra. When the tour died down and wound up in California, George decided to stay. He made Los Angeles his home for the rest of his life.

The mid to late 1960’s were a very busy period for Smith. Muddy Waters asked him to join his band again in 1966 after James Cotton left. George toured and recorded with this band for a year. These recordings however did not feature Muddy himself. In 1968 he teamed up with a young harp player named Rod Piazza. Soon they started playing and recording together with their band, Bacon Fat. During the next few years Smith recorded a handful of albums, some of these sides were with the members of Bacon Fat. Smith also recorded as a sideman with various artists during this period.

The mid to late 1960’s were a very busy period for Smith. Muddy Waters asked him to join his band again in 1966 after James Cotton left. George toured and recorded with this band for a year. These recordings however did not feature Muddy himself. In 1968 he teamed up with a young harp player named Rod Piazza. Soon they started playing and recording together with their band, Bacon Fat. During the next few years Smith recorded a handful of albums, some of these sides were with the members of Bacon Fat. Smith also recorded as a sideman with various artists during this period.

All of this slowed down in the 1970’s. Recording opportunities were becoming scarce. When he did record, it was mainly as a sideman. In 1977, George met another young harp player who would wind up being among his most celebrated students. This player was the late, great William Clarke. Throughout the remainder of Smith’s life, George and William Clarke were close friends. They performed together whenever they could, and recorded together in the early 1980’s.

When he did record, it was mainly as a sideman. In 1977, George met another young harp player who would wind up being among his most celebrated students. This player was the late, great William Clarke. Throughout the remainder of Smith’s life, George and William Clarke were close friends. They performed together whenever they could, and recorded together in the early 1980’s.

Although Rod Piazza and William Clarke were two of the more celebrated young players whose careers have impacted by Smith’s tutelage, his influence fell over many of the younger players of the time. He was willing to help anyone who was in need of guidance. These relationships seem to have a positive impact on Smith’s life and career as well. There are many stories of him asking younger harp players to perform or travel with him. Smith’s legacy is indelibly tied to this generosity. George “Harmonica” Smith died of heart disease on October 2, 1983. He will never be forgotten.

Copyright 2022 BLUES JUNCTION Productions. All rights reserved.

BLUES JUNCTION Productions

7343 El Camino Real

Suite 327

Atascadero, CA 93422-4697

info